POLA NEGRI BIOGRAPHY

by David Gasten

|

Young Pola Negri in the Polish stage production of Sumurun. |

The following biography was commissioned by La Cinémathèque Française in Paris, France, for a week-long career retrospective of Pola Negri's movies at which took place there on April 7-12, 2010. An abridged version of this biography was translated into French and used for the museum's website and promotional materials; this is the longer version orignal with a few minor improvements. We extend our gratitute to La Cinémathèque Française and to restropective organizer Cyrille Langendorff for allowing us to use the biography here.

Pola Negri was born Barbara Apollonia Chalupiec on January 3, 1897 in Lipno, Poland, (at that time part of the Russian Empire) to a mother of impoverished Polish royalty and a father of Slovakian ancestry. She was the youngest of three children, but because the first two children died young, she grew up an only child.

Pola’s mother, whose maiden name was Eleonora Kietczewska, was distanced from her family in part because of her choice to marry Jerzy Chalupec, the man she loved, instead of into opulence. They were married on July 10, 1892. Eleanora used part of her inheritance to buy her husband a tin factory in Lipno. Pola’s life began very unassuming, with her father running the tin factory and her mother staying at home. Pola was a loner and loved to climb trees and sit in the branches alone, which earned her the affectionate name “Zamyslona” (meditator) from her father. One time she fell from her perch and was temporarily struck blind in the accident; a surgery in a German hospital restored her to health. Eleanora was a devoutly religious Polish Catholic, so when she and her husband were testing Pola’s eyesight through reading as she was healing after the surgery, she reportedly told her husband to have Pola read out of the Bible “so that she’ll be a good girl”. Eleonora passed her devotion to the Catholic religion to Pola, which the latter would particularly embrace in her later years.

Just as Eleonora was devoted to religion, her husband Jerzy was devoted to the cause of political freedom. Poland has had a history of being dominated by either Germany or Russia, and at the time Poland was under the occupation of Imperial Russia. There were many underground political groups who were looking to replace the Imperial rule with a Polish populist government, and Jerzy belonged to a group that hoped to place an American-style democratic government over Poland. Jerzy would take long leaves from the tin factory to Warsaw for this, leading Eleonora to believe that he was seeing another woman. The true story was revealed when Russian troops took Jerzy from his home and to prison for his treasonous revolutionary activities. Eleonora depleted her inheritance further on lawyers to try to have his case appealed, but to no avail. Pola saw her daddy two more times, once in prison and once when Russian forces were taking him away to a prison camp in Siberia. To make matters worse, after Jerzy was released from prison following World War I, he did not return to his family but abandoned them for a younger mistress, whom he would later marry. This loss and betrayal of her father left a wound in Pola’s heart that she would carry with her for the rest of her life.

|

Pola in the 1920's with her mother, Eleanora Chalupec. |

With the loss of her husband, Eleonora spent the remainder of her inheritance on a grocery store that failed, and after that ran a struggling catering business. She and Pola moved to Warsaw, took residency in a miserable flat in the ghetto, and Pola attended Catholic school. It was as a child playing in the streets that he received her first “break”. Two singers in the Polish Imperial Opera saw Pola playing, and, taking note of her natural physical grace, arranged for her to try out for the Imperial Ballet. Pola was accepted and began training as a dancer, while being tutored in her academic studies by a teacher in the afternoons. Thus began a rigorous training regimen that would later lead Sam Goldwyn to refer to her as “the hardest working actress in Hollywood”.

Pola made her dancing debut as one of the chorus of baby swans in Tchichovsky’s Swan Lake. She continued to play occasional chorus and minor roles, and finally was chosen for a solo role in Saint-Léon ballet Coppélia. All this time, Pola suffered from delicate health, and when she contracted tuberculosis after this small triumph, it closed the door on her ballet career forever.

It was about this time that Casmir de Hulewicz, vice president of the Imperial Theater, had taken notice in Pola’s talent. Hulewicz happened to be a former beau to Pola’s mother as well as a friend of Pola’s idol Sarah Bernhardt. This began a long relationship with Hulewicz playing benefactor and unofficial male guardian to Pola and her mother. Hulewicz financed Pola’s stay at a sanatorium so that she could recover. It was there that Pola discovered the works of Italian poet Ada Negri, and after a reading of Negri’s poetry met an enthusiastic audience response at the sanatorium, Pola decided to pursue a career as an actress.

Hulewicz and Pola’s mother initially did not approve of her new career aspirations, so Pola conspired with her French tutor to audition for the Warsaw Imperial Academy of Dramatic Arts (under the same roof as the Imperial Ballet) under the assumed name Pola Negri. The audition was successful, and both of her guardians agreed to the career change. Pola was a fast and diligent study, and after a year of preparation, she graduated from the theater academy in 1914 at the age of 17. Her graduating performance was as Hedwig in Ibsen’s The Wild Duck, which instantly resulted in offers to join a number of the prominent theatres in Warsaw. Her benefactor Hulewicz helped her play the demand wisely, having her accept larger roles in one of the smaller theaters, which opened offers for better roles in the larger theaters. Meanwhile, Pola’s well-developed star power organically attracted a fanatical following that quickly made her a sensation in the Warsaw theatre.

The art of the motion picture was in its infancy at this time, and Polish film entrepreneur Alexander Hertz signed her to a contract with his Sphinx Film Company. Pola found herself shooting movies with Sphinx in the days and rehearsing and performing in the theater at night. Her first Sphinx film was Niewolnica Zmyslów (Slave to Her Senses, 1914), which also has the distinction of being the first feature film made in Poland. Many of Pola’s film appearances with Sphinx were short subjects, and included amongst other things a short detective serial, one episode of which was rediscovered in an Italian archive in 2009.

Pola’s next break came when she appeared as the dancing girl in a Polish production of Sumurun, a play based on one of the Arabian Nights stories. Sumurun had been a triumph for the world famous theater director Max Reinhardt in Berlin’s Deutsches Theater. An assistant director of Reinhardt’s that happened to be Polish directed the Polish revival of the play, and Reinhardt was considering a revival of the play in Berlin. Based on the assistant director’s recommendation, a still-teenage Pola traveled to Berlin to audition for the dancing girl role and was offered the part.

Pola’s Polish film success also led to roles with German independent Saturn Films; Wenn das Herz in Haß erglüht (If the Heart Burns With Hate, 1917) is the only one of her six films with them known to survive. This led to a contract with UFA, Germany’s leading film studio. Among her first films for UFA was Der gelbe Schein (The Yellow Ticket, 1917), a German remake of one of Pola’s Polish short subjects depicting the sordid life of Jews in the oppressive slum environment of imperial Russia.

Pola in one of the elaborate sequences in the Ernst Lubitsch-directed Madame DuBarry (1919), the film that catapulted the pair into international stardom. |

It was in the Max Reinhardt theatre production of Sumurun that Pola met Ernst Lubitsch. Lubitsch was also working as a director of comedy shorts at UFA, and convinced UFA to invest in an elaborate costume drama that starred Pola Negri. The film was called Die Augen der Mumie Ma (The Eyes of the Mummy, 1918) and led to a series of costume film collaborations featuring Negri and Lubitsch that would each become more expensive and successful than the previous. The next was Carmen (1918), which was then followed by Madame DuBarry (1919). It was during this time that Pola had her first marriage, a short-lived arrangement with the Count Eugene Dambski.

Madame Dubarry was a success throughout the world and made international stars of both Lubitsch and Negri. The film brought down the post-World War I ban on German films in America, and began an international demand for German films that was so strong that in the early 1920’s, it appeared that Berlin would overshadow Hollywood as the film capital of the world. A distraught Hollywood responded to this overseas threat by trying to buy out their European competition, and Ernst Lubitsch and Pola Negri were the first director and star that they would buy out. This would be the beginning of a very long line of European film people imported into Hollywood, which would famously include Greta Garbo, Ingrid and Ingmar Bergman, Alfred Hitchcock, and many others. Lubitsch was sent for first when Mary Pickford decided that she wanted to appear in a European-style costume film of her own—this would end up being the unjustly maligned Rosita (1923). Interests in Hollywood then began a bidding war for Pola Negri’s services, and Paramount Pictures ended up winning the bid. Pola set sail for Hollywood, arriving on September 12, 1922.

Pola’s first film for Paramount would be Bella Donna (1923), which would be one of only a handful of films in which Pola would ever play a true “vamp” role. The film would be the first of many that would attempt to fashion Pola into an Americanized idea of what European sophistication was, and would also parade Pola through a long series of opulent fashions and clothing changes. In two years’ time, Pola’s Americanized continental mystique was starting to wear thin with some of the American public, so the screenwriters took advantage of this to create the brilliant part-comedy Woman of the World (1925), which contrasted Pola’s European sophistication with the down-to-earth environment of small-town America for comedic and dramatic effect.

When Pola wasn’t working on a new film, she was making headlines the world over for a string of celebrity love affairs, beginning with Charlie Chaplin, and continuing with Rod La Rocque and Rudolph Valentino. Circa 1926, Paramount gave Pola an image makeover by casting her as more relatable proletarian characters in the context of a European fantasy world. Initially this makeover was successful, but it was Pola’s love life that would turn against her and keep this new improved Pola from realizing her full potential. Pola had been Valentino’s amour at the time of his death in 1926, and infamously put on the worst performance of her career at Valentino’s New York funeral. When Pola followed this with a rebound marriage to Georgian prince Serge Mdivani in 1927, the American public turned on her to the point that her masterpiece Barbed Wire (1927) sunk at the box office in America, although the film fared well in Europe and elsewhere.

Pola had purchased the beautiful Château de Rueil-Séraincourt in Vigny, France, before leaving for America in 1922. When her contract came up for renewal with Paramount in 1928, Pola was newly married and expecting a baby. She decided to retire from films and move into the Château to devote herself to her husband and new child. A few months later, she miscarried and sunk into a deep depression and alcoholism. Pola’s mother encouraged her to return to acting, and she ended up accepting an offer to appear in a film to be released by Gaumont British in England. Initially the English playwright George Bernard Shaw was going to license the film rights to his play Cesar and Cleopatra, but when the rights to the play proved to be too expensive for the budget, the production company opted for an original modern story, and employed the German director Paul Czinner to direct. Although an English-produced film, the resulting movie The Woman He Scorned (1929) was a masterpiece in German-style filmmaking of the period, recalling similarly directed films such as F. W. Murnau’s Sunrise (1927) and Hedy Lamarr’s Ekstase (1933). The Woman He Scorned would be Pola’s final silent film.

|

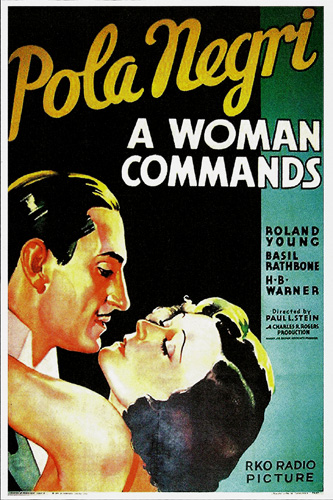

Pola Negri with Basil Rathbone in a promotional poster for the RKO Radio film A Woman Commands (1932). |

After the success of The Woman He Scorned, the French directorial team of Tony Lekain and Gaston Ravel planned to feature Pola in their film Le collier de la reine (The Queen’s Necklace), which would become France’s first talking film. Pola’s husband forbade her to appear in the film because it would require her to be nude from the waist up. Meanwhile back in Hollywood, RKO called for Negri’s services in what would be her first talking film, A Woman Commands (1932). The film itself failed, but Pola’s appearance singing the song “Paradise” became a runaway hit, and went on to become a minor standard for a number of years. Negri was booked for a vaudeville singing tour to promote the film, and then appeared in the touring theatrical production A Trip to Pressburg. Negri collapsed from gall bladder inflammation after the production’s stop in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and was unable to complete the tour. The French directorial pair of Lekain and Ravel then contacted Pola again to appear in Fanatisme (1934), and this time the recently divorced Pola was able to accept the role. The historical drama about Napoléon III would be Pola’s only French film.

Pola’s next international success would be the German-produced film Mazurka (1935), directed by Willi Forst. The film led to Pola receiving a contract with her old studio UFA, which led to five more German-made feature films, including Moskau-Shanghai (1936) and Tango Notturno (1937). Pola continued to live in France while she made her German films, but after the oppression of the Nazi regime became too much to bear, she decided to leave France and return to the United States, where she joined in the massive emigration of Europeans to the States via a ship sailing from Lisbon.

Back in Hollywood, she appeared in one more film, the anti-war comedy Hi Diddle Diddle (1943), before retiring from films for good and spending her remaining years in San Antonio, Texas, coming out of retirement once in 1963 to appear in the Disney film The Moon-Spinners. Pola died on August 1, 1987 in San Antonio, Texas at the age of 90, having left a legacy of superlative performances and many “firsts” for the movies.