|

The |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

| Home |

Music in Silent

Films Section Tom

Verlaine and Jimmy Rip: A

DVD review by David Gasten

Of

all the films of the silent era, experimental silent shorts are the

farthest ahead of their time, and have a timeless look and feel to them,

as though they could have been made today just as well as in the 1920’s.

Occasionally the outfits and hairstyles of the people in the films

will give away their time period, but otherwise many a film student has

since created the exact same types of films as we see here. And because of their

timeless and abstract nature, experimental silents are also the most receptive to

treatment with modern soundtracks. Modern

silent film soundtracks cover the gamut in style, genre, and

instrumentation, and the results

vary just as widely. But what

is rare is for a specialty film distributor to be so impressed with a set

of silent film soundtracks that they elect to release them advertised

under the name of the soundtrack artist rather than under the names

of the films or filmmakers. But

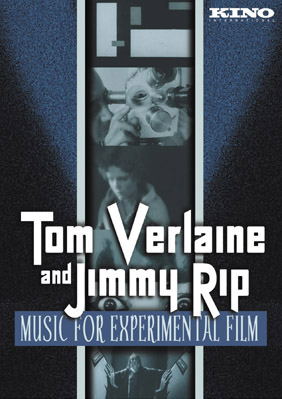

that is exactly what has happened in the case of Kino Video’s release of

Tom Verlaine and Jimmy Rip: Music for Experimental Film. About

Tom Verlaine

Here’s a little background on guitarist Tom Verlaine, the primary musician behind these soundtracks. Verlaine was not known at all as a silent film soundtrack composer until relatively recently. He is best known as the founder and frontman of the 1970’s new wave band Television, a band that not only broke the new wave music phenomenon worldwide, but also broke the legendary and highly influential New York punk rock scene. Television were the first band to popularize the famous CBGB’s club, a New York music venue which would subsequently become the pop music legend and the merchandising powerhouse that it is today. CBGB’s was initially intended to showcase “Country, Bluegrass, and Blues” (hence the name), but instead went on to split the bill with the club Max’s Kansas City as the hub for New York’s “happening” punk rock/new wave music scene of the late 1970’s. That music scene would go on to give us Blondie, The Ramones, Talking Heads, The Patti Smith Group, Suicide, and many other famous and influential pop music groups. It also contributed to creating a whole new way of looking at and creating music that is still with us today, for better or for worse. Although Television only lasted long enough to create two albums

initially, Tom Verlaine went on to start a solo career as a new

wave/college rock performer, further developing the style Television was

exploring in their tenure together. Verlaine

retained a loyal following and critical favor over the years, but kept a

larger following in Europe than in his American homeland, where he seemed

to be talked about more than he was actually listened to.

Most

of Verlaine’s material has been full-band, electric rock music with

Verlaine singing somewhat off-tune and supplying a quirky guitar sound that would be

mimicked by many college rock performers that followed him. But in 1992, Verlaine diverted from this pattern by

releasing an all-instrumental, late-night ambient record entitled Warm

and Cool. Warm and Cool is

still a full-band album, as Verlaine recruited ex-members of Television

and The Patti Smith Group to assist on bass guitar and drums, but this

time the focus here was on atmospheric, Spaghetti Western soundtrack-influenced guitar sounds in an instrumental jazz and/or rock

setting. On Warm and Cool,

Verlaine created pop-song length compositions that would present a

relatively simple musical motif, and draw the listener in by presenting

the motif in a vast, nocturnal type of atmosphere perfect for all-night

driving excursions. Some of

the music is essentially free rock (i.e. the rock equivalent of free

jazz), but even these pieces have a somewhat relaxed nighttime feel to

them. Apparently this album

was something of a rejuvenation to Tom Verlaine’s career, as it sold

better than his other albums in America (thanks in large part to the

support and promotion of Rykodisc, the record label who released it), and

would lead to a full-fledged reunion of Television, complete with the

release of a third Television album.

But Verlaine’s experimentation with atmospheric instrumental guitar music was only beginning with Warm and Cool. Verlaine began working with session musician and producer Jimmy Rip on creating music made exclusively with guitars to score experimental silent short films. The duo then performed these soundtracks live in Europe and in America in the late 1990’s. In the ensuing years, the duo have perfected their work into a beautiful collection of soundtracks that led Kino Video to release the 78-minute DVD Tom Verlaine and Jimmy Rip: Music for Experimental Film. And this is despite the fact that Kino has previously released much more comprehensive avant-garde compilations that included every last one of these films! The resulting DVD is not only a collection of beautiful music set to film, but also the most concise and pleasant introduction to experimental silent shorts you could hope to find anywhere. About

the Soundtracks

The

soundtracks of Tom Verlaine and Jimmy Rip feature Verlaine on lead guitar,

and Rip on rhythm guitar and atmospherics.

What sets the duo’s soundtracks apart from many other modern

silent film soundtracks is as follows.

First, they understand that they are there to support the film, not

vice versa. Despite what you

would think (and what the title of the DVD suggests), Verlaine and Rip do

not have a self-indulgent, “the artistes are here” attitude in

their performances. The two

understand the importance of underscoring the film and putting the film

first. Second of all, they purposely create music that is beautiful

and atmospheric, rather than ugly, trashy, and postmodern.

In doing so, they make the films seem less “artsy” and “experimental”, and

more like a series of beautiful dreams that you do not want to wake up

from. Romantic

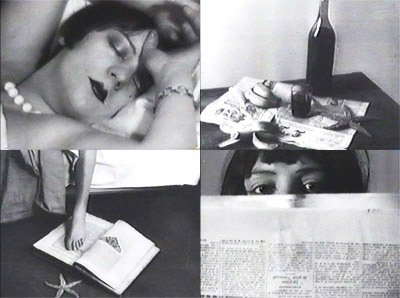

Dreams and Poems: L’Etoile de Mer and Brumes D’Automne Man

Ray’s L’Etoile de Mer (1928) opens the DVD.

It is the best example of how Verlaine and Rip successfully elevate

an experimental silent film to that of a romantic dream that you do not

want to end. L’Etoile de

Mer concentrates on atmosphere and emotion rather than on a storyline,

and succeeds gallantly in portraying the emotion of love.

L’Etoile de Mer attempts to illustrate a poem written by

the surrealist poet Robert Desnos,

using the consistent visual of a starfish (which the poem calls a

“flower of glass”) to illustrate the love a woman has given to a

man. The man studies it and cherishes the woman and the love that

she has left in his heart, as consistently illustrated by the starfish,

only to have the woman leave him for another man.

But even though she is absent, her love is still with the man and

he still cherishes the memory of that love, even though the woman herself

is gone. And yet even the

heartache seems so beautiful, because of the powerful memory of the love

that the woman has left with him. The film opens and closes with a jewel

box-like door opening and closing, and when the jewel box door closes, you

feel a satisfying “That’s all folks” resolution, but also feel like

the alarm clock has just gone off and that it’s now time to get up, get

ready for work, and leave the beautiful, romantic dream behind.

Verlaine

and Rip create a heavenly, ice-paradise aura around L’Etoile de Mer,

one that makes you feel like you are personally falling in love with the

woman illustrated in the movie. Verlaine’s

initial melody lines are like a love song a man might serenade a woman

with, but the melodies change and float with the film wherever it wants to go,

becoming almost violin-like at times.

Rip’s atmospherics are celestial and vibrant, although still cold

and icy to illustrate the distant, outside-looking-in detachment and

longing portrayed throughout the film.

While

creating this atmosphere, the duo add other sounds that get across other

themes in the film. They

create sophisticated but appropriate “chug, chug, toot, toot” sounds

for the trains and the ships when they appear in the film, add a

fast-strumming dissonance to illustrate the sexual tension when the woman

leads the man up to her room and then immediately sends him away, and

create strong, gong-like pulses on the low end of the guitar that

correspond with the shattering glass around the portrait of the woman that

illustrates the man’s anger at having the woman leave him.

Brumes

D’Automne

(1929) is

a film directed by French resident and Estonian émigré Dimitri Kirsanoff.

Kirsanoff was an early independent filmmaker who developed his own

style and technique without being aware of the other French avant grade

filmmakers of his period, at least initially.

Apparently Kirsanoff has a whole body of fantastic work that to

this day has yet to be completely rediscovered.

Like

Man Ray, Kirsanoff takes a poetic approach to his filmmaking, but chooses to use a more

cohesive (if fragmentary and minimalistic) storyline. Kirsanoff tell

this story with one

actress (Kirsanoff’s first wife Nadia Sibirskaïa, whom he would use

repeatedly in his short films, and who would go on to play roles in a

couple of Jean Renoir movies); brief, faceless glimpses of one male actor;

and a series of naturalistic settings, all with no intertitles whatsoever. The

story goes like this: It is autumn, the leaves are falling, it’s raining

outside, and the days are getting shorter and colder.

A girl receives a “Dear John” (or is that a “Dear Jane?”)

letter from the man she loves. She

remembers the last time she saw him and how she had agreed to wait for

him—and now he has left her, so she ended up waiting for nothing.

She is heartbroken and proceeds to burn all of his letters. The smoke from the burning letters goes out of the chimney

and into the crisp autumn air, forever lost and never to return.

She then goes out walking in the fallen leaves, draped in a large

shawl. She comes upon a lake,

and considers suicide, the cold lake beckoning her to her death like a

chorus of male sirens. But

she picks herself up and keeps walking, as the leaves in the trees above

her fall and float away in the water, almost as if they are carrying the

initial strains of heartbreak away with them.

The end. Although

Brumes D’Automne concentrates more on a moment of lost love, the

film is still quite romantic, as it gazes lovingly upon the actress and

plunges the viewer headfirst into her world and her emotions.

We want to wrap our arms around the actress and let her cry in our

bosom, but obviously this is not to be; the only comfort she has is the

large, warm shawl that is wrapped around her.

For this film, Verlaine improvises over a subtle tick-tock pulsing

provided by Rip that gives us an ever-present sense of the falling rain

and the falling leaves. Again,

the film is romantic but cold at the same time, which repeats the theme of

longing that comes across so well in L’Etoile de Mer.

Verlaine and Rip prepare you for the sequence where the actress

considers suicide by starting the suspense when she walks out the door,

and then building it up, letting you hear and feel the lake calling out to

her as she becomes delirious, and then returning to the gentle, pulsing

tick-tock of the rain and leaves when she shakes off the thoughts of

suicide and keeps walking. Like

I say, these are definitely experimental silent films you could play for

your girlfriend—just don’t tell her that it’s “experimental

film”. J

Expressionist

stories: The

Fall of the House of Usher and Where Verlaine and Rip are most effective in underscoring a film is where the film is telling a story, namely in The Fall of the House of Usher and The Life and Death of 9413, a Hollywood Extra (both from 1928). These two films are both essentially American recreations of German expressionism. Despite their twisted and non-realistic images, German expressionist films always use their distorted imagery to tell a story, and neither of these films is an exception to that rule. Both of these films' storylines are easy to follow and only slightly more abstract than regular German expressionist films. The strong imagery and equally strong storylines give the duo a much broader canvas to work with.

The Fall of the House of Usher (1928) is a film created by James Sibley Watson, Jr. and Melville Weber. Watson was an heir to the Western Union telegraph empire, and financed and collaborated with co-director Weber on this and another film absent from this collection entitled Lot in Sodom (1933). If you are interested in reading some background information on these films from the eyewitness of someone who was there and working for them, visit this page. The film

retells the famous Edgar Allen Poe horror story without using any

intertitles and with the aid of powerful expressionist visuals that still

pack a strong punch eighty years later.

Verlaine and Rip take a minimalistic, suspenseful approach to

scoring this film, mimicking the real or imagined sounds of the plodding

horse, the platter of death served to Madeline Usher, the dropping rain,

the falling hammers, the ripping casket, and finally the crashing castle

and swirling moon and lake at the end of the film.

Most of the soundtrack relies on a heartbeat-like “buh-boom, buh-boom”

rhythm that grows into a Jaws-like back-and-forth

step between two half-notes, which is then interjected with notes that

pound suddenly and without warning like pangs from a migraine headache.

Meanwhile, the lead guitar hovers and swirls over and around these

sounds like a crying, moaning ghost reliving its own execution.

At times the music compliments the movie so well that you

completely forget that it is there and assume that the sound you are

hearing is the sound the film itself is making.

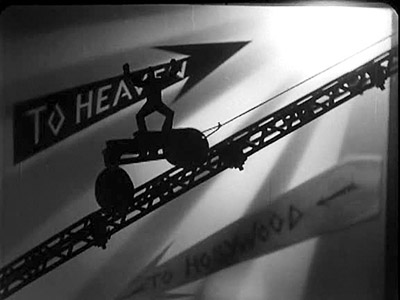

The visuals here look like a Vanity Fair magazine cover from the period brought to life, this being interspersed with live shots of buildings, studio lots, spotlights, and a limousine pulling up at a gala movie premier. Verlaine and Rip score the film’s beginning with a happy-go-lucky, walking “duuum bop, duuum bop” tune as the uninitiated extra-to-be arrives in Hollywood, only to show up at a studio and have the number “9413” etched onto his forehead, which the musical duo emulates by scratching the guitar strings. The duo go on to emulate the “blah blah blah” talking movements the actors make with their faces with a half-kazoo and half-tuba “wah wah” sound similar to (but lower in pinch than) the “wah wah” sounds the off-screen adults make in the classic Peanuts cartoons. As the extra starts looking for work and the “‘No Casting Today’—the story of my life” reality starts setting in, the music reflects this by becoming drab and dreary. In the meantime, two of 9413’s competing extras go on to success, #13 (a lady) as a regular supporting actress, and #15 (a man) as a star. As the trumpets signal #15's newfound success, the guitars jangle excitedly and parade behind the clamor of new star’s acclaim and entrance into the bourgeois.

When poor 9413 is

shriveling away in his apartment as the bills start pouring in, he makes

one last attempt to call in for work, only to hear one final “No Casting

Today”. As this happens, the music spells out 9413’s certain fate to the point where

you are almost brought to tears as poor 9413 sinks to the floor and

perishes before your eyes. But

as 9413’s contemporaries on Earth laugh at his fate, 9413 rises from

his grave and is transported into heaven,

where he loses his number, finds casting as an angel, and flies away into

the heavenlies. The music

begins with swirling, brutal crashing, and rises up and up like a jet plane

with 9413’s ascension through the celestial tiers, finally ending in a high-pitched crystalline tinkling as 9413 flies into the film's similarly crystalline art deco portrayal of heaven. Sounds

like incredible viewing, doesn’t it?

That’s because it is! Verlaine

and Rip’s takes on The Fall of the House of Usher and Hollywood

Extra are two overwhelming viewing experiences that are an incredible

way to spend a half-hour of your life and almost worth the DVD’s $20 US price tag by themselves.

Where’s

the documentary?: Rhythmus 21

Rhythmus

21 (1921) is quite a fun movie to watch, because the film

itself plays like a long signature animation that might open a 1960’s

documentary. Verlaine and Rip

run with this concept, making the film look like exactly that.

The guitars echo beautifully with a hollow, hummable motif that

could easily be from the Warm and Cool album, while rectangular

shapes grow, shrink, and change places and color (the colors being black,

white, and gray, of course) before your eyes.

You almost expect a vintage travelog about the Swedish countryside

with muffled, William Burroughs-like narration to begin rolling

afterwards. At three minutes, this film is a delight to watch because of its brevity and

because of its extremely minimalistic (and for some of us, nostalgic)

feel. An

interesting side note: the Rhythmus 21 soundtrack has the honor of

being the only one of these soundtracks that was actually recorded in the

studio, as all of the others were taken from live concert recordings in

Europe. The Rhythmus 21

soundtrack was engineered by Verlaine’s Television bandmate Fred Smith,

who also appears as the bass player on most of the Warm and Cool album.

Random

Images: Emak-Bakia and Ballet Mécanique The

film soundtracks that are not quite as memorable are the ones where the

film itself is little more than a series of random images.

Man Ray’s Emak-Bakia (1926) is one of two examples

of this. In Emak-Bakia, the images have no rhyme or reason to them,

as Ray appears to be just playing around with various effects, so Verlaine

and Rip have no choice but to just improvise music behind it. However, they do manage to keep the music composed-sounding

rather than improvised. Because

the music the duo create is so good, it ends up overpowering the film, exposing the

film’s inherent weakness in being nothing more than a random string of images.

But

even here, when the musicians have a strong visual, they get behind it, such as the

sequence where they tap the guitar strings as wooden shapes start popping

up into the form of a castle, or the sequence where they scratch the

guitar strings as a man tears off his collar and throws it into a pile of

torn collars, and the collars in the pile suddenly start falling up and

out of the picture. Also, when the director depicts a ride in a car, the

music suddenly starts to cruise along with the car, and when the film

alternates between a man strumming a banjo and a lady dancing the

Charleston, the guitars suddenly mimic the frenetic, rhythmic banjo

playing. So it’s certainly

not for a lack of trying on the musicians’ part that the soundtrack is

not as strong, it’s just that the film itself is not that strong to

begin wtih and

therefore the musicians cannot get behind it properly.

Ballet

Mécanique

(1924)

gives the musicians even less to work with, essentially being a string of

prism and globe effects and back and forth cuts of various images,

primarily metal items. A

surreal, dismembered-looking stop-motion Charlie Chaplin makes an

appearance at the beginning and at the end, and a girl looks through their

overused kaleidoscopic lens and makes faces at us, but otherwise there’s really not a

lot to it. Verlaine and Rip

try to drive home the busyness of the film, but that’s about all they

can do with a series of random images

that are more rhythmic in feel but even less engaging than Emak-Bakia.

By the way, all of these films were provided by the Raymond Rohauer collection, and each film opens with a “From the Rohauer Collection” title card. Veraline adds a short ascending signature ditty every single time this title card rolls that is guaranteed to stick in your head.Summary (P.S. For more information on the musical career of Tom Verlaine, visit www.thewonder.co.uk, a UK-based Tom Verlaine fansite.)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pola

Documentary: Life is a Dream in Cinema Now on DVD! |

|||||||||||||||||||||||