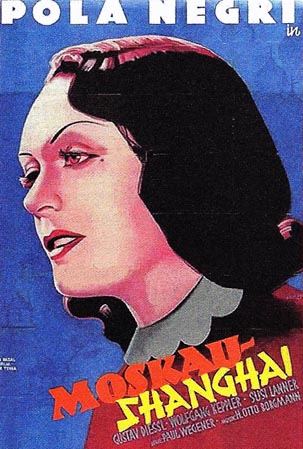

Pola Negri in MOSKAU-SHANGHAI (Moscow-Shanghai, 1936)

|

A beautiful promotional poster for Pola's German film Moskau-Shanghai (1936), directed by her former Sumurun co-star Paul Wegener. |

by Frank Noack

Article written

March 17, 2011; published August 18, 2011

Initially I wasn't too keen on watching Moskau-Shanghai (1936), and wouldn't have looked out for it in the first place if it hadn't starred Pola. The stills were far from stimulating, and Pola's costumes and hair seemed never more than adequate, not bad but not as breathtaking as befits a star of her magnitude. I had the title song “Mein Herz hat Heimweh” (“My Heart Is Homesick”), sung by her, on CD, and found it rather uninspiring. Fortunately, the film I saw on March 16, 2011 in Berlin's Eva-Lichtspiele turned out to be a minor delight.

The story begins in 1917, in Moscow, with Pola introduced during a ball as widowed beauty Olga, wooed by two men, Sergei (Gustav Diessl) and Alexander (Wolfgang Keppler). She likes the former and loves the latter. She also has a little daughter from her late husband, Maria. Traveling far from home because she has to sell an estate, she is caught in the chaos of revolution and can't return to Moscow. By accident, she meets nobleman officer Alexander on a crowded train station who helps her escape from the Bolshevik authorities. They marry and pretend to be simple peasants. Also by accident, Sergei turns up, who has joined the Bolsheviks. He seems to have become a bad guy, denouncing Alexander as a nobleman and cold-bloodedly shooting him in his cell. Nobody realizes that the execution was faked, that Sergei actually helped the former rival escape. Now it is Sergei who escorts Olga to freedom, to Shanghai.

About ten years later, in Shanghai, Olga tries to make some money as a cabaret singer, but her song is too depressing for the customers, and she is booed. But she doesn't have to work, Sergei being a wealthy Russian exile. She just misses her daughter and her husband. During an Easter festivity, Olga and Sergei listen to a male choir and discover Alexander among the singers. Olga faints; she and her great love are reunited. Unselfish Sergei is happy for both of them. But more problems await Olga. Alexander has, in the meantime, met a girl with whom he has fallen in love, and whom he intends to marry. She is none other than Olga's lost daughter, Maria.

Alexander decides to give up Maria since, after all, she is still young and can fall in love again with someone else whereas Olga ... this is charitably not spelled out but Olga is not young anymore and has a double chin and is of sturdy built. Indeed, the film is suspiciously shy of close-ups for its leading lady. Fortunately for all involved, Alexander doesn't have to give up the girl because Olga gives him up, and this is not too big a sacrifice, since the dashing Sergei has been waiting at her side all the time.

There remains one sacrifice, frustrating and incomprehensible for the modern viewer. Olga, like Vera in Mazurka, doesn't want her own daughter to know that she is her mother. Why, for heaven's sake? Unlike Vera, Olga hasn't sinned. She just has been intimate with her future son-in-love. Which, of course, was a sin back then. But the girl would be much happier if she knew her mother is still alive.

Cameraman Franz Weihmayr uses oppressive lighting and atmosphere to drive home the mesage of Pola's torch song “Mein Herz hat Heimweh” (“My Heart Is Homesick”) in Moskau-Shanghai (1936). |

What makes this film so likeable is the contrast between grotesque subject matter on the one hand, and restrained acting, directing and scoring on the other. Olga loses everything, her estate, her daughter, her husband, and is constantly on the run, but apart from one short fainting, she remains in good humour. Each time she is in trouble, an attractive man turns up to help her. Somehow, this film anticipates Pola's own lucky escape from war-torn Europe.

Right from the beginning, the film is incredibly fast-paced without appearing hysterical. Its assured and elliptical storytelling reminded me of Richard Boleslawski's 1935 version of Les Miserables; back then filmmakers knew how to tell a rich story quickly. Veteran actor-director Paul Wegener, born in 1874, was a well-known lover of both Russia and Far-East Asia, which explains this Nazi German film's unusually sensitive depiction of its Moscow and Shanghai locations. Best of all, Wegener makes little use of the plot's anti-communist potential. And Pola is immensely relaxed and likeable throughout, even if the film as a whole is not a must for Pola lovers. It is obvious that there have been logistical problems: How to portray a woman who is no longer a ravishing beauty, and not yet a monster of the latter-day Crawford-Davis kind. As a result, Pola's great scenes seem a bit shy and evasive.

Hans-Otto Borgmann's score is unusually sophisticated by 1930’s standards, and contains lots of different, subtle themes. Franz Weihmayr's excellent lighting suggests he has seen Josef von Sternberg's The Scarlet Empress which, by the way, did better business in Germany than in the US. And never did Pola in her 1930s German period have such handsome leading men. Albrecht Schoenhals (Mazurka, Tango Notturno) and Ferdinand Marian (Madame Bovary) were dashing but also a bit creepy. In contrast, Gustav Diessl (star of several G.W. Pabst films) and Wolfgang Keppler look like love gods, handsome and virile and trustworthy, too.

Austrian actress Susi Lanner has little to do as Olga's daughter, but she is intense and funny, without any hint of sentimentality. Lanner was as lucky as Pola: When the Nazis invaded Austria, she happened to know a US business man who took her with him, to become his wife. She would die in New York in 2006, at the age of 94.